On The Money

I earned my Cuba stripes in the heyday of the convertible cuban peso - the CUC. It was one of the allures of visiting the island - the batshit idea of a dual currency: one for the locals, one for the tourists. [1] You can thank Patrick Magee of the Irish Republican Army for the CUC: the bomb he planted at The Grand Hotel in Brighton, in 1984, missed its intended target - the former British PM Maggie Thatcher. After her survival, Thatcher bonded with Mikhail Gorbachev - the Russian leader who put a pin in the former Soviet Union and an end to the Cold War. Castro’s beard had been milk-stained having heretofore been sucking on the teat of Mother Russia to support itself in spite of the US blockade. But the collapse of the USSR ended Cuba’s lifeline and there wasn’t another wet nurse around for Castro to lock his lips on to. And so the CUC was born. A currency that existed only in Cuba and to be used by the tourists the island was now encouraging to visit. CUC for the visitors. The peso cubano (CUP) for the locals.

The CUC was pegged to the dollar, mostly. No financial institutions exchanged the currency outside of Cuba, so visitors had to bring their own country’s money and exchange it upon arrival. If you hadn’t spend the last centavo before departing, that money was worthless. Hotels, restaurants and supermarkets only accepted CUC and the prices were set accordingly, meaning the locals, who were paid in CUP, could rarely afford basic items and simple luxuries.

After many years of visiting and always giving my last CUC to Lafonda’s family upon departure, I decided, in 2018, to keep a few hundred CUC for the next visit, which would have likely been the following year. I hadn’t counted on Covid-19 keeping us away for a total of five. Nor had I envisioned that in 2021, the Cuban Government would scrap the CUC - effectively turning my CUC into Monopoly money.

But at least Miguel Díaz-Canel Bermúdez’s replacement system foregoes the tourism apartheid that inevitably grew as a result of a two-currency system; now Cuba has just one very simple currency for all to use.

Or not.

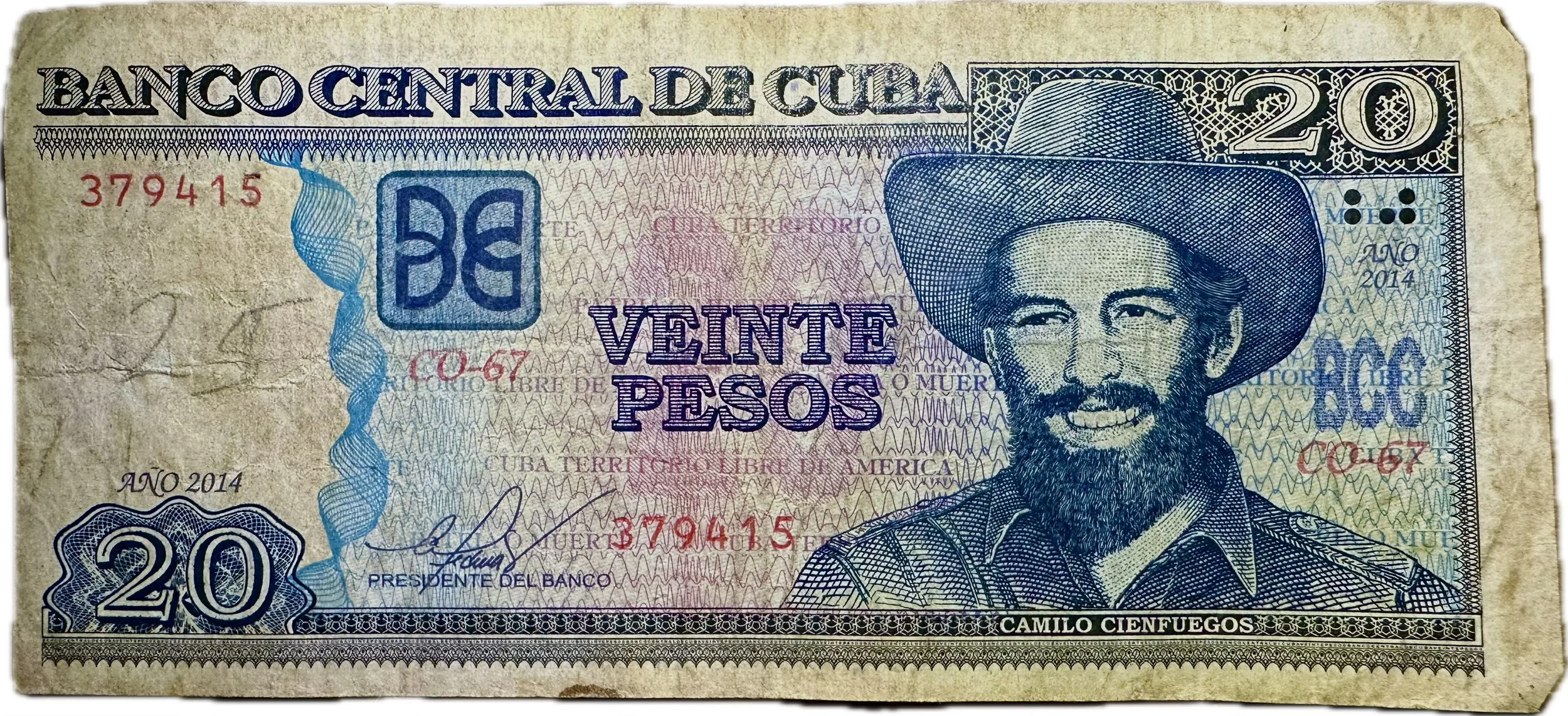

The new system - presumably one the Cuban government thought was better than having the cuban peso and the CUC, literally has locals longing for the good old days of the dual currency. The offical single currency is indeed the Cuban peso - worth exactly bobbins and also not available to exchange outside of Cuba.

In July 2023, one Euro could buy 120 pesos cubanos at the Cuban banks or casa de cambios. But, if you were prepared to change money on the street - and practically every Cuban on the street was offering this service - you could get 180 to 200 pesos. How trusting are you? And if the thought of being ripped off is not enough of a headache, consider this: in reality Cuba is now a triple or quadruple currency because, while the government-owned hotels and restaurants will only officially accept pesos cubans as payment, everywhere else will accept one of the following:

pesos cubanos

USD

Euros

Canadian Dollar

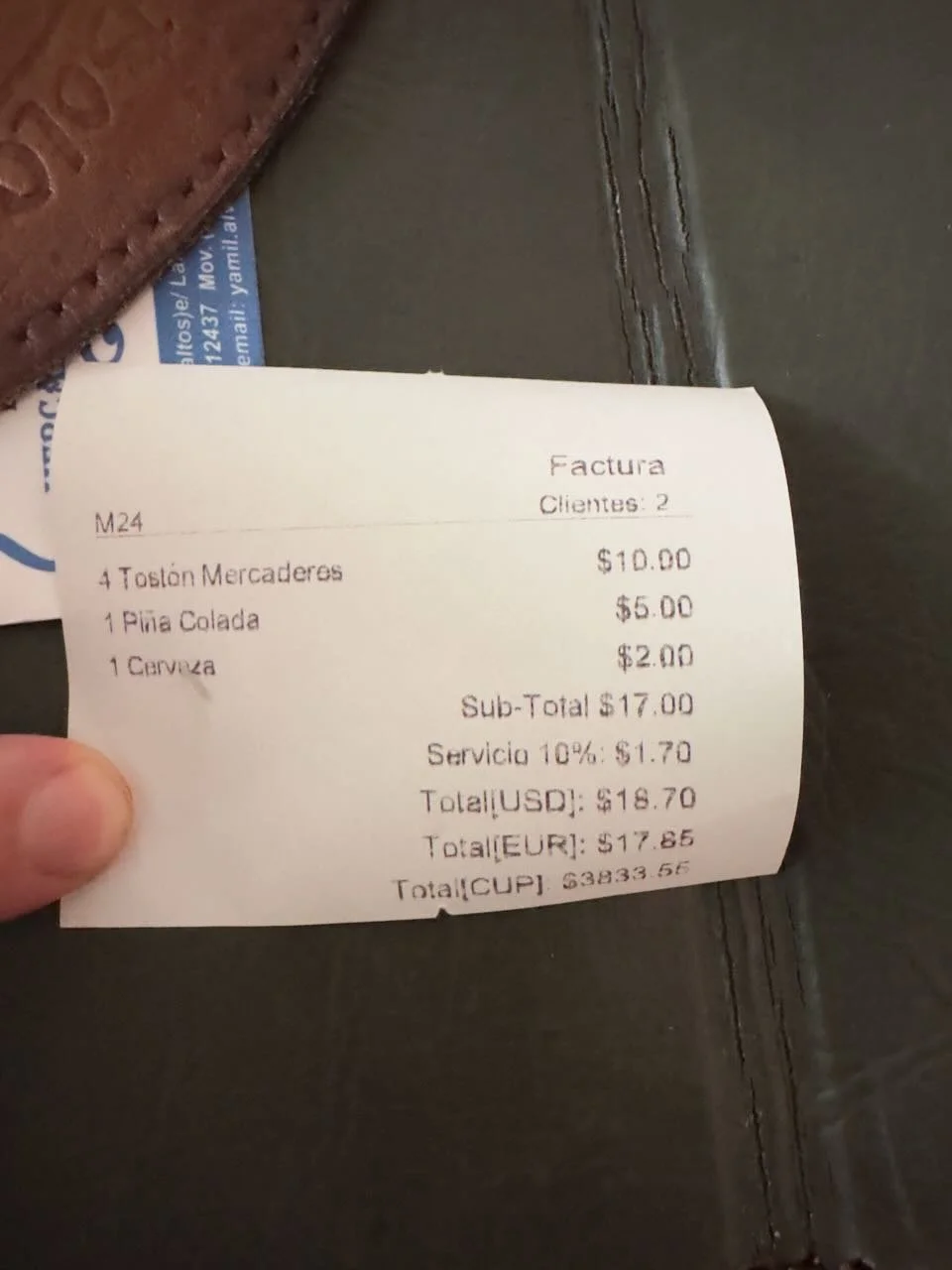

Restaurants will gladly accept any of the above, but they won’t exchange it at street value; it will be better value than the official exchange rate of 120 pesos. It was usually around 150 to 160 pesos. But they also won’t always differentiate between the value of USD and Euro. So if you pay with the higher value Euro, you lose out. Better value is had, therefore, by exchanging your foreign currency on the street with a Tony Montana and carrying with you a wedge of notes thicker than the Malecón sea wall.

Exchanging money on the black market can also be more hassle than it’s worth. By day two of our trip we still hadn’t exchanged our Euros. Federico - Lafonda’s uncle - insisted he could exchange the money for us and even ominously warned that it would be dangerous for us to attempt doing so on the street. Best gives me the money, he repeatedly Gollumed. Instead, we took our Euros to that most bankable of black market locations: a government sanctioned hotel. In the mocha-hued lobby of the Melia Habana, they’re less welcoming of blow-ins than they used to be. Security were all over Lafonda and I, whereas a few years before they wouldn’t have minded non-guests to enter.

We ventured one floor down the spiral staircase to the cafe on the ground floor where there are less security guards and more opportunities for the wait staff to do deals. Inside the cafe we ordered a cafe cubano and a sandwich de jamón y queso each and only then learned that the hotel wouldn’t accept Euros. Only CUP or card. Inside the waitress's position on this was steadfast. So we took a seat outside at a high table in the courtyard, next to the water fountain - the noise of which echoed loudly around. The fountain must have been useful to the employees to hold covert conversations such as the one we were about to have with the waitress. Once settled in our seats, the waitress appeared before us with a helpful suggestion: she’d make an exception and allow us to pay in Euros after all. This meant, of course, that our order would never be rung up on the cash register; it would be split between her and the chef. Likely with her other co-workers. Knowing this, we checked the rate.

“$120 pesos, mamí,” she replied. Matter of fact.

Lafonda was a former waitress at the Comedoro, further along the coastline. She has a scar on the back of her right ear from a time she panicked inside the walk-in fridge having shoved a giant flank of beef down her shirt to take home. She slipped and cracked her head but still managed to keep the beef.

Lafonda understood the system and told the waitress she knew what was happening. Since this was el mercado negro we wanted street rates.

“Eschuchame,” the waitress said, irritated. “120 is the hotel rate. ¿Que puedo hacer?

At this point the conversation became less amicable and I decided to focus intently on the eating of my sandwich, which, owing to how dry and miserable it was, required huge powers of will to finish. Experience has taught me that when two Cubanas speak in raised voices and increasingly lengthy sentences, it’s best to bunker down until it blows over. Much like Cuba’s hurricanes in September.

Lafonda’s argument, rightly, was that the hotel’s exchange rate was irrelevant when negotiating a black market deal. The waitress’s logic made no sense: we were in the hotel, and the hotel’s rate was 120. Nevertheless, she stood firm. So did Lafonda. After an eternity of folded arms and eyeballing one another, Lafonda, who would rival Michael Jackson for surgery if the amount of times she cut off her nose to spite her face was literal, opted to pay for the food with her bank card, thus not only paying the hotel rate, but also incurring an international transaction fee for her troubles.

Only the Cuban government gained in this transaction. The waitress got zero. Lafonda paid over the odds. And I finished that miserable sandwich to the last crumb.

Still. A short while later, once the everyone had cooled off, we approached the waitress again and arranged to exchange 50 Euros with her at the more charitable rate - though not street rate - of 180 pesos cubanos. It tided us over for a day and then we repeated the saga elsewhere.

[1] Of course, not considering myself a tourist, I tried to explain to customs officials upon my arrival that they should probably issue me a special card so that I could more easily obtain and spend the cuban peso. Alas, they didn’t understand me.